BORDER HEALTH

According to the U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration, if the border region were to be made the 51st state, the U.S.-Mexico border region would:

- Rank last in access to health care;

- Second in death rates due to hepatitis;

- Third in deaths related to diabetes;

- Last in per capita income;

- First in the numbers of school children living in poverty; and

- First in the numbers of children who are uninsured.

Challenges in New Mexico, as a border state, are vast and complex. The border region is defined as 100 kilometers on either side of the international boundary. Martinez (1994) classifies U.S.-Mexico border residents as nationalists, uniculturists, binationalists, biculturasits, transient migrants, settler migrants, transnationals, and assimilationists based on their ethnic or cultural identity, consumerism, travel within, to and from both sides of the border, and adoption of values. Thus, the entire state of New Mexico is profoundly affected by migratory patterns as the movement of community residents is often fluid between two nations. This cultural landscape is greatly defined and influenced by perceptions that span these two nations and effect norms of wellness, illness and health care, further complicating the development of a health care system that fully serves a binational, multicultural setting.

Economic and education inequalities and health disparities are concentrated in the US-Mexico border region. The unemployment rate in the border region is about 250 to 300% higher than rest of the U.S. Those who are unemployed or under employed often live without health insurance, contributing to the high number of uninsured in New Mexico (New Mexico Voices for Children, 2007). About 350,000 people reside in colonias, which are unincorporated neighborhoods often lacking basic services such as running water and septic/sewage systems (CHC Border Health Policy Forum, 2006). Undocumented community members are fearful to access preventative health care due to recent raids in many colonias, causing illegal immigrants to go underground. This culmination of mounting health disparities, extreme poverty, lack of health insurance and high numbers of immigrants not accessing health care until a crisis arises are critical issues for the public health sector.

Communities on both sides of the U.S. Mexico border region experience high rates of infectious diseases such as tuberculosis and food borne illness and, share the ten leading causes of mortality namely, cardiovascular disease, cancer, unintentional injuries, diabetes, cerebrovascular disease, COPD, pneumonia and influenza, chronic liver disease and cirrhosis (Healthy Border, 2010). In general, Hispanics including Mexican Americans are at risk for chronic health conditions based on data collected regarding leading health indicators such as physical activity, obesity, tobacco and substance use, sexual risk behavior, injury and violence prevention, environmental health, access to care and immunizations (Kandula, Kersey & Lurie, 2004). Diabetes, Obesity, teen births, maternal and child health, homicide, tobacco and alcohol use and, homicide prevail as health disparities in NM with teen births, diabetes, obesity, Chlamydia, Hepatitis B and, drug and alcohol related deaths measured as “unacceptable levels of disparities”.

Due to the rural nature of the state, there is a lack of access points for health care. Although preventative health care is recommended, a cancer diagnosis requires specialized care. Since affordable public transportation is rare in many rural border communities and specialized care often needs to be accessed in hubs like Albuquerque and Las Cruces, it is unattainable for many individuals. Nearly all of the counties in New Mexico are designated as health professional shortage areas. It is difficult for rural counties to finance round-the-clock health care practitioners. Furthermore, it is difficult to keep health care professionals that are not originally from the community as they often experience personal and professional isolation. At the same time, community members may not access health care from providers considered “outside” of the community because the provider may lack cultural sensitivity and language barriers.

HEROs contribute to addressing inequity and disparity by:

- Being place-based to better understand overall context

- Contributing to local solutions

- Leading capacity building efforts as an employee, community and family member

- Gaining an in-depth understanding of the nuances that contribute to disparity

- Critical thinking and applied professions that have the ability to grasp and problem solve multifactorial health issues

“US-Mexico Border

Center of Excellence

Consortium”

“Kids Count:

Data Snapshot on

High-Poverty Communities”

“New Mexico

Progress Report”

“Educational Attainment

in the United States”

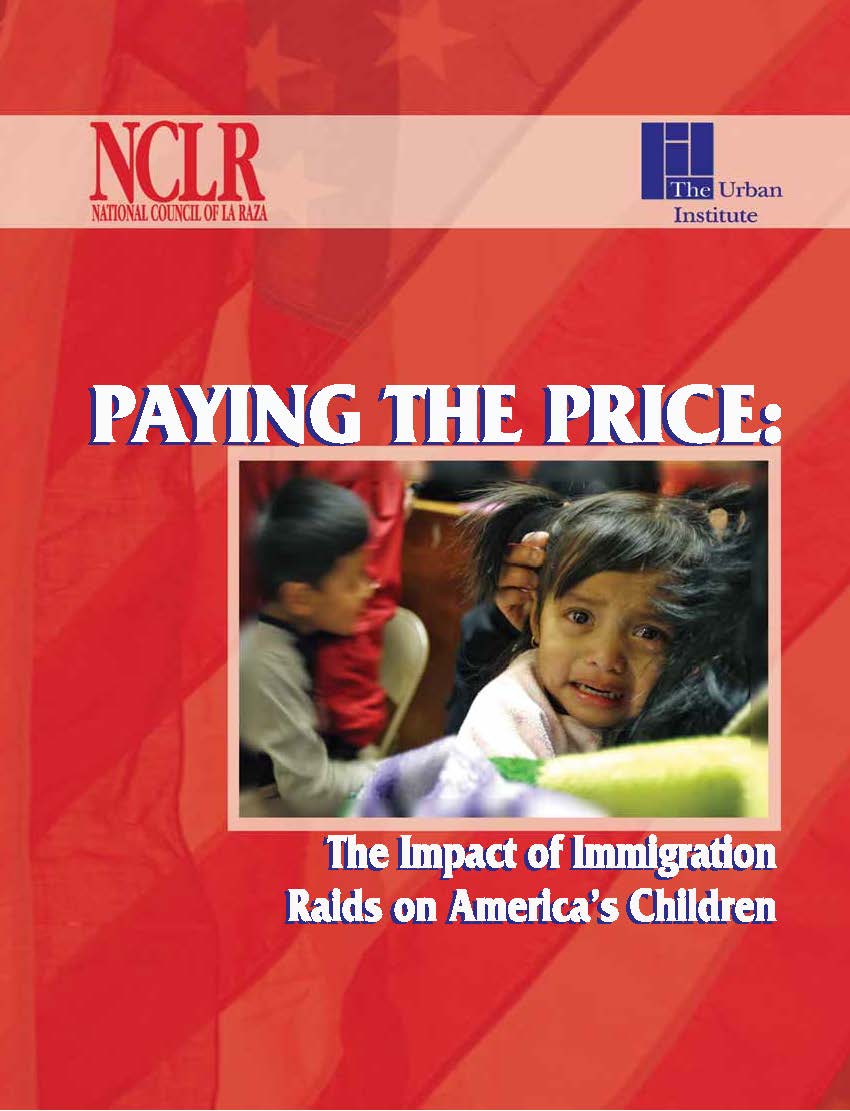

“Paying the Price:

The Impact of

Immigration Raids

on America’s Children”