Academic Health Centers: The Social Mission of AHCs

Academic health centers (AHCs) often have complicated relationships with communities who, in turn, often feel ambivalent about the role of AHCs vis-a-vis their communities. At times there is considerable distrust. Many times communities see the AHC come when there is a grant, and leave when the grant goes away. There seems no long term commitment or investment in local needs. In fact, many communities feel resentment that their priorities, their wisdom and expertise are not elicited when the AHC proposes a project or research opportunity.

Academic health centers (AHCs) often have complicated relationships with communities who, in turn, often feel ambivalent about the role of AHCs vis-a-vis their communities. At times there is considerable distrust. Many times communities see the AHC come when there is a grant, and leave when the grant goes away. There seems no long term commitment or investment in local needs. In fact, many communities feel resentment that their priorities, their wisdom and expertise are not elicited when the AHC proposes a project or research opportunity.

Health Extension, community-based and offering a long-term commitment to link community priorities with AHC resources offers a bridge toward greater university-community trust. Academic health centers resources are siloed into colleges, departments, and administrative offices or they are siloed between different mission areas—education, service or research. But the health needs of communities, hospitals and primary care practices are broad, often spanning all of these silos. It is thus the role of Health Extension to serve their communities by tapping into all the relevant “silos” and to monitor their effectiveness, giving feedback to the academic health center.

To shift locus of control of programs from AHC to community and to facilitate the effectiveness of Health Extension in bridging the silos, UNM HSC has come up with several strategies. One is a single, unifying vision for all components of the HSC called “Vision 2020: Working with community partners, UNM HSC will help New Mexico make more progress in health and health equity than any other state by 2020.” Vision 2020 is bolstered by performance plans incorporating outcomes of the Vision and by a set of metrics (such measures as prevalence of chronic disease, access to care, educational attainment) in all the “silo” areas comparing NM to other states at the state and county level. Achieving improvement in those metrics requires collaboration not only with community partners but collaboration across the HSC.

Cooperative Extension Service: Diffusion of Innovation

The Cooperative Extension model was built upon a partnership between university faculty subject area experts and agricultural producers. Historically, and still today, the local agents live and work within the communities they serve. This relationship builds trust and is one of the key components to the success of Cooperative Extension. This level of trust is where many University Health Centers fall short.

The Cooperative Extension model was built upon a partnership between university faculty subject area experts and agricultural producers. Historically, and still today, the local agents live and work within the communities they serve. This relationship builds trust and is one of the key components to the success of Cooperative Extension. This level of trust is where many University Health Centers fall short.

Health Extension based out of Academic Health Centers are partnering with their Cooperative Extension compatriots in promoting health in local communities or counties. They, too, are responding to communities identifying their own, local health needs and mobilizing university resources address those needs.

Working together, Cooperative and Health Extension are offering each other a bi-directional benefit. With only 10-15% of community health being affected by the healthcare system, both are addressing the far more influential “social determinants” of health in their communities. Cooperative Extension is sharing its knowledge and programs in food security, food safety and access to healthy foods. Both are sharing the creation of urban gardens and assisting impoverished rural communities create food pantries and grow fresh fruits and vegetables for local consumption and sale.

Public Health: Building on Complementary Strengths

“Public health is everything outside our skin— individual health is everything within”.

“Public health is everything outside our skin— individual health is everything within”.The world around us impacts our health in countless ways. Each bite of food we take, sip of water we drink, the air we breathe, the condition of the house we live in, the safety of roads and sidewalks near our home, school, or work—all impact our own health and the health of our family, neighborhood, city, state, nation and the world we live in. A quick scan of the daily news brings home the fact that public health is a global issue–a measles case in New Delhi can travel by plane and expose a stream of travelers in major airports in London, New York, and Los Angeles in a single day. Within our own community, if we want to understand why two 4-year-olds with similar asthma severity have very different rates of hospitalization, medication compliance, and respiratory health outcomes, we must be willing to look beyond each child’s individual health condition, and explore factors in the home, family, neighborhood, and community. Addressing these factors requires different tools, skills and interventions.

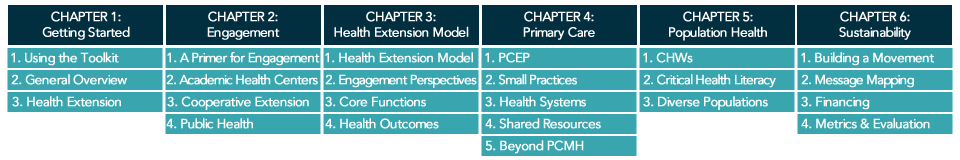

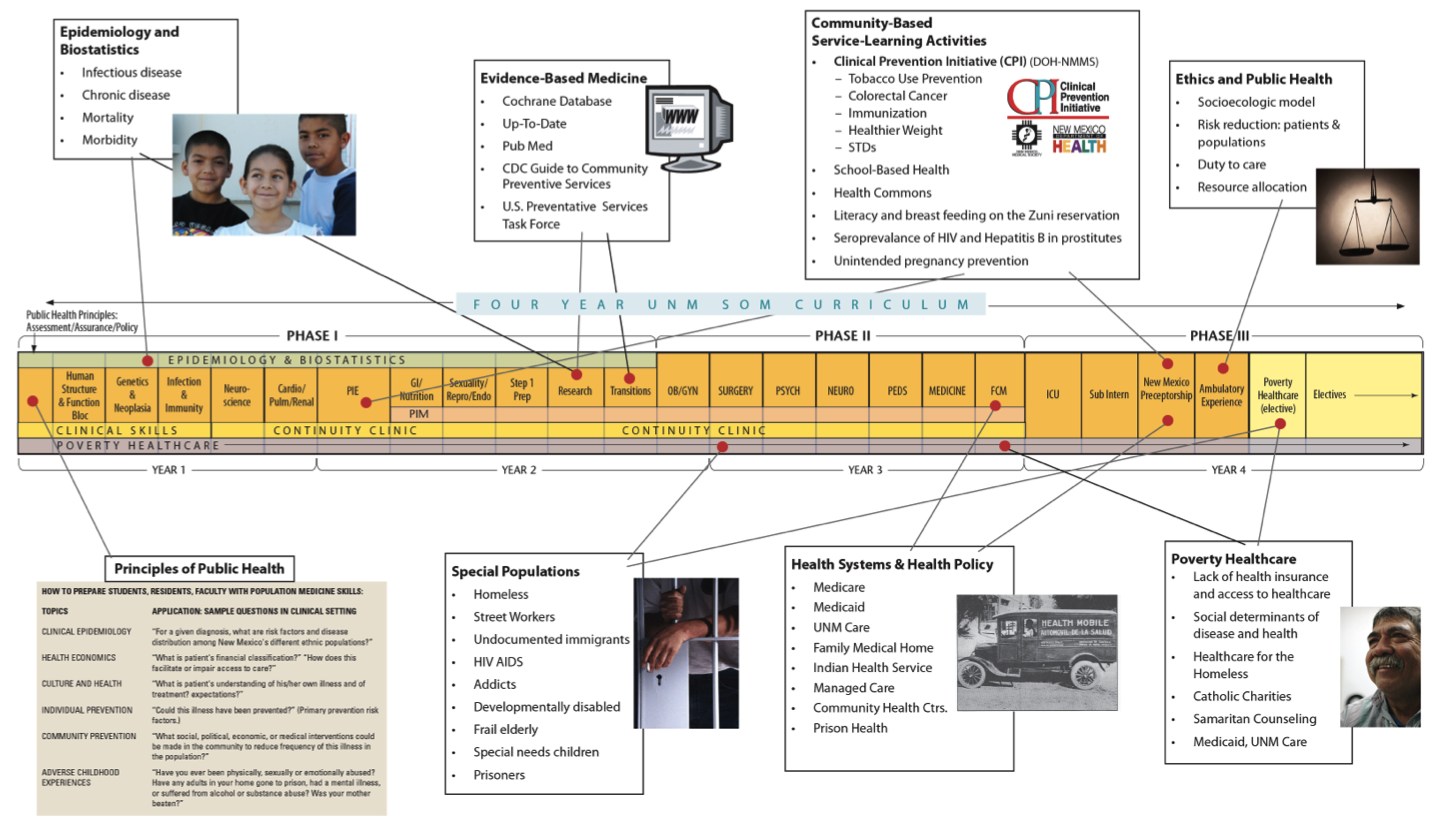

Broader skills for health professionals to address community health is embedded in UNM’s public health certificate, required for all medical students and family medicine residents. HEROs serve to link these learners to community groups and programs. Click below to view a timeline of UNM’s public health certificate program.

Primary Care/Health Systems: Best Practices for the Triple Aim

Health extension can interact with primary care and health systems in many ways: Health Extension as primary care practice transformation coaches; as enhancers of practice-based research networks in improving primary care practice quality; as brokers of a variety of shared, regional resources for many small, local primary care practices; as connectors between Cooperative Extension and primary care practices; and as leaders of social determinants of health and disease within the health system and community.

Health extension can interact with primary care and health systems in many ways: Health Extension as primary care practice transformation coaches; as enhancers of practice-based research networks in improving primary care practice quality; as brokers of a variety of shared, regional resources for many small, local primary care practices; as connectors between Cooperative Extension and primary care practices; and as leaders of social determinants of health and disease within the health system and community.

Health extension emphasizes “growing our own” workforce with regard to geographic locality and ethnicity as a strategy to address access to care. It is more likely that local trainees will be culturally competent and work locally. Black and Hispanic physicians are about 5 times more likely to care for patients of the same ethnicity, which demonstrates the need for “growing our own”.

With an eye toward the broader role for front line, primary care practices in society, some health extension agents have promoted training and education on the principles of the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion and the World Health Organization’s primary care documents.