The Social Mission of the Academic Health Centers

The UNM HSC Vision 2020 – “University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center will work with community partners to help New Mexico make more progress in health and health equity than any other state by 2020” came from the leadership of the HSC as a way to support the improved health of New Mexico communities.

The UNM HSC Vision 2020 – “University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center will work with community partners to help New Mexico make more progress in health and health equity than any other state by 2020” came from the leadership of the HSC as a way to support the improved health of New Mexico communities.

We will do this by focusing on evidence-based interventions and evidence-informed policy, by disseminating and building on successful programs and pilots, and by linking and aligning existing resources to address community priorities for improving health and health equity.

This is part of a national movement for Academic Health Centers to measure their success by the health of the communities they serve. An institutional commitment through the adoption of the vision has been an essential piece of this goal, as well as the integration of this vision into the work of all the colleges, departments, and offices.

As a concrete example of how an AHC responded to an identified community need experienced in New Mexico, many elderly do not have transportation to drop off/pick-up and consult with a pharmacist about their medications, including prescriptions, over-the-counter, herbal, etc. A HERO agent coordinated a brown-bag session at a local community center for pharmacy faculty and students to provide a 1-on-1 session for seniors to address polypharmacy issues and concerns, with coordinated scheduled individualized appointments on-site at the senior center. This response to a community need prevented possible polypharmacy issues by informing and advising seniors about their medications.

Tapping the Resources of the Academic Health Center

To shift locus of control of programs from AHC to community and to facilitate the effectiveness of Health Extension in bridging the silos, UNM HSC has come up with several strategies. One is a single, unifying vision for all components of the HSC called “Vision 2020: Working with community partners, UNM HSC will help New Mexico make more progress in health and health equity than any other state by 2020.” Vision 2020 is bolstered by performance plans incorporating outcomes of the Vision and by a set of metrics (such measures as prevalence of chronic disease, access to care, educational attainment) in all the “silo” areas comparing NM to other states at the state and county level. Achieving improvement in those metrics requires collaboration not only with community partners but collaboration across the HSC. Click below to watch a short video about Vision 2020:

Research for Discovery & Problem-Solving

The HEROs health extension program sought ways of bridging this gap between community health and university research priorities. Approximately half of the academic health centers in the U.S. received substantial awards to establish Clinical Translational Science Centers (CTSCs). An important aspect of the CTSC is to hasten the translation of scientific discoveries to their practical application in patient care. In addition, the priority health needs of patients and communities should help drive the research enterprise of academic health centers. To receive such an award, therefore, each applicant submitted a component related to “community engaged research.” The University of New Mexico received such an award and in its community engaged research component, it described the HERO program and its bi-directional role in connecting communities with researchers. The CTSC then decided to fund one HERO FTE to support 10% of 10 different HEROs around the state. The MOU establishing this relationship between HEROs and the CTSC contains the following language:

Educating the Health Workforce

Another key element of educating the health workforce is offering ample opportunities to serve in the community. The following video describes an initiative developed with the assistance of health extension, in which health sciences students arose to serve the community, assisting with the school immunization project.

Clinical Service: Serving People & Communities

Health Extension can help practices go beyond the PCMH by applying some of the same practice facilitation approaches to amplifying that transformation to an impact on the helath of the community served by that practice. This can take many forms and a practice can seek outside help in the process, tapping into shared resources serving the region. The importance of this broader approach is clarified by a recognition that for every patient seen in practice with a chronic condition, there may be 5-10 people in the community with the same condition not being seen or treated. Health Extension can reach out to community members through distribution of refrigerator magnets with the telephone number of the 24/7 statewide nurse advice line. When called, the line can offer those without a medical home appointments in primary care sites near the caller’s home. Another intervention is to link primary care clinics to local public health clinics where public health nurses can offer parents who bring children for free immunizations can be linked with medical homes. And finally, the Health Extension agent can work to improve the health literacy of the community through articles in local papers, interviews on local radio or TV and sharing clear, simple messages critical to the health of their community with individuals with high population contact such as ministers or hair dressers.

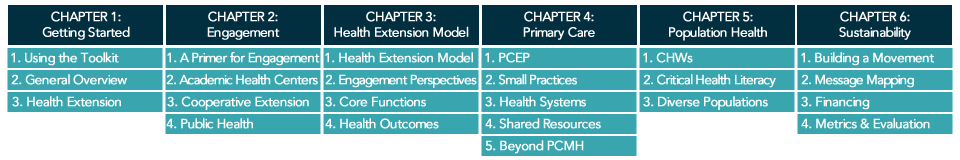

Related Literature & Tools