Defining Engagement

“Community engagement is the collaboration between institutions of higher education and their larger communities (local, regional/state, national, global) for the mutually beneficial exchange of knowledge and resources in a context of partnership and reciprocity.

Carnegie Foundation

“An Engaged Institution… is fully committed to direct, two-way interaction with communities and other external constituencies through the development, exchange, and application of knowledge, information and expertise for mutual benefit.”

American Association of State Colleges and Universities, Task Force on Public Engagement

“(Engaged Scholarship is) a specific conception of faculty work that connects the intellectual assets of the institution (i.e. faculty expertise) to public issues such as community, social, cultural, human, and economic development. Through engaged forms of teaching and research, faculty apply their academic expertise to public purposes, as a way of contribution to the fulfillment pf the core mission of the institution.”

Barbara Holland, University of Sydney

“Engagement is the partnership of university knowledge and resources with those of the public and private sectors to, enrich scholarship and research, enhance curricular content and process, prepare citizen scholars, endorse democratic values and civic responsibility, address critical societal issues, and contribute to the public good.”

Committee on Institutional Cooperation

The Imperative for Engagement: Leadership & Policy

Universities and institution of higher education can participate in the Engagement Academy, a “unique executive development program is designed for leaders responsible for developing institutional capacity for community engagement. Participants will develop institutional plans for engagement and will return to their campuses with the ability to advance their plan as well as effectively link community engagement to the teaching, research, and service missions of the institution.” Click below to learn more about this program:

Are you Engaged? Take the Test!

Extension for Engagement: How Extension Reflects the Values of an Engaged Institution

COMING SOON, STAY TUNED! (video vignette from Oregon partners on the shift from “transfer of expertise” to “sharing and reciprocity”)

Engaged Scholarship: Integrated Knowledge that WORKS

Some of the types of community-engaged scholarship include:

- Service-learning

- Community-Bases Participatory Research (CBPR)

- Academic public health practice

Engaging faculty in the community through scholarship leads to many important goals that are important to academic health centers:

- Improve health professional education

- Achieve a diverse health workforce

- Increase access to care

- Eliminate health disparites

Working with communities is important work for faculty. However, in order to be considered scholarship, the following must exist:

- Clear goals

- Adequate preparation

- Appropriate methods

- Significant results

- Effective presentation

- Reflective critique

- Rigor

- Peer review

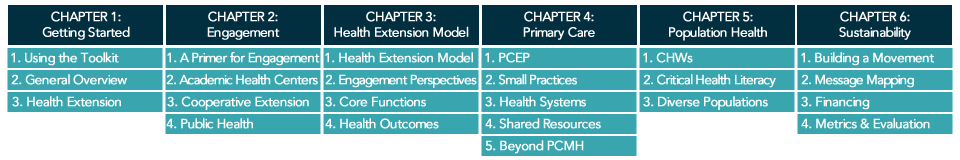

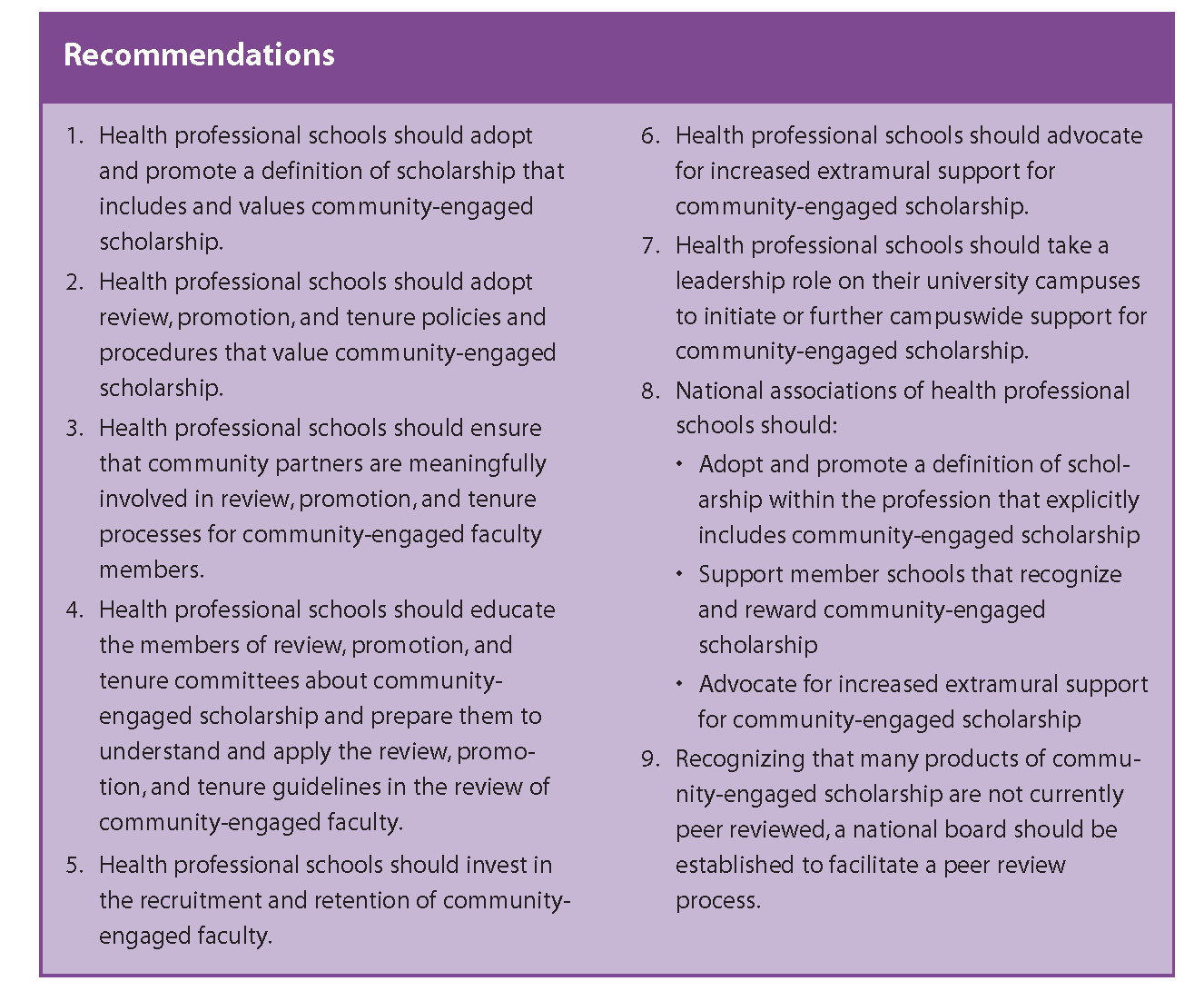

To learn more on how Academic Health Centers can support community-engaged scholarship, click on the table below:

The Clinical and Translational Science Awards Consortium has compiled the following principles of community engagement:

- Be clear about the purposes or goals of the engagement.

- Become knowledgeable about the community’s culture, economic conditions, social networks, political and power structures, norms and values, history, and experience with efforts by outside groups to engage it in various programs.

- Go to the community, establish relationships, build trust, work with the formal and informal leadership.

- No external entity should assume it can bestow on a community the power to act in its own self-interest.

- Partnering with the community is necessary to create change and improve health.

- All aspects of community engagement must recognize and respect the diversity of the community. Awareness of the various cultures of a community and other factors affecting diversity must be paramount in planning, designing, and implementing approaches to engaging a community.

- Community engagement can only be sustained by identifying and mobilizing community assets and strengths and by developing the community’s capacity and resources to make decisions and take action.

- Organizations that wish to engage a community as well as individuals seeking to effect change must be prepared to release control of actions or interventions to the community and be flexible enough to meet its changing needs.

- Community collaboration requires long-term commitment by the engaging organization and its partners.

The full document can be found in “Related Literature and Tools”, below.

Community Engaged Policy

There must also be structures in place within colleges and departments that allow for long-term relationships with community partners built on trust and mutual benefit. This requires students, faculty, and staff work on priorities and projects that are important to and beneficial to the community. To do this leadership must recognize that timelines may be delayed, recognition of the community partners needs to be prioritized, and the power differential between academic institutions and community members and organizations be recognized and discussed.

The HSC engaged communities in a process to receive feedback on their partnerships; the summary of recommendations that lead to effective and meaningful engagement include the following

Related Literature & Tools

“Linking Scholarship & Community:

Report of the Commission on Community- Engaged Scholarship in the Health Professions”

The following presentation may also be useful tools in learning about engagement:

“Scholarship-Focused Outreach and Engagement: Aligning Institutional Capacity with Engaged Scholarship”

There are several other key articles and tools you may find useful. Click on the links below to access them:

- “Leading Organizational Change: A Comparison of County and Campus Views of Extension Engagement”

- “Shaping Communities Through Extension Programs”

- “Rousing the People on the Land: The Roots of the Educational Organizing Tradition in Extension Work”

- “Community Engaged Scholarship Toolkit”

- “Report of the UNC Taskforce on Future Promotion and Tenure Policies & Practices”