Aligning Aims & Targets for Population Health Improvement

This expanded scope is taking on greater relevance as health care reform highlights the importance of a population health perspective. Accountable Care Organizations focus attention on improving health care value and health outcomes for a defined population. There is growing appreciation that the acute and chronic illnesses of patients seen in primary care, especially in underserved communities, is reflective of the “downstream” consequence of social and economic factors such as poverty, low educational attainment, poor housing, unsafe neighborhoods, unhealthy food choices and inadequate social support (Marmot, Woolf).

This expanded scope is taking on greater relevance as health care reform highlights the importance of a population health perspective. Accountable Care Organizations focus attention on improving health care value and health outcomes for a defined population. There is growing appreciation that the acute and chronic illnesses of patients seen in primary care, especially in underserved communities, is reflective of the “downstream” consequence of social and economic factors such as poverty, low educational attainment, poor housing, unsafe neighborhoods, unhealthy food choices and inadequate social support (Marmot, Woolf).

The Institute of Medicine Committee on the Integration of Primary Care and Public Health, released in March, 2012, stresses the need to develop a stronger partnership between primary care clinicians and public health departments to collaboratively address these fundamental determinants of health and illness and to improve population health. Health Extension agents can play a critical role in this endeavor.

Below is a video prepared by the Bernalillo County Health Council describing how these factors relate to health:

Interfaces with Public Health across Mission Areas

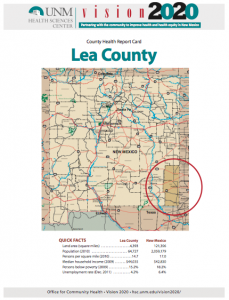

HERO agents work with two programs of vital importance to primary care and public health. Agents work with their local Department of Health Offices to produce annual County Health Report Cards for each of the state’s 33 counties and uses these report cards to monitor progress towards state community health goals for 2020.

HERO agents work with two programs of vital importance to primary care and public health. Agents work with their local Department of Health Offices to produce annual County Health Report Cards for each of the state’s 33 counties and uses these report cards to monitor progress towards state community health goals for 2020.

Another example of this bridging work has been HEROs’ promotion of the nation’s only 24/7 statewide nurse advice line (1-877-725-2552). The Line is supported by a public-private partnership. It receives 15,000 calls per month and has significantly reduced unnecessary ER visits, allowed rural primary care physicians to turn over their night telephone calls to the Line nurses, and allowed the New Mexico Department of Health to monitor on the Line’s web-based call data entries, patterns of symptoms across the state, picking up early warning symptoms of communicable disease symptoms.

Another example of this bridging work has been HEROs’ promotion of the nation’s only 24/7 statewide nurse advice line (1-877-725-2552). The Line is supported by a public-private partnership. It receives 15,000 calls per month and has significantly reduced unnecessary ER visits, allowed rural primary care physicians to turn over their night telephone calls to the Line nurses, and allowed the New Mexico Department of Health to monitor on the Line’s web-based call data entries, patterns of symptoms across the state, picking up early warning symptoms of communicable disease symptoms.

Training the Health Workforce in Public Health

We should worry–a 2005 assessment of the public health workforce in six states by Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) before recession-related cuts in state and county budgets found that the public health workforce was understaffed, underpaid, lacking formal training in public health, and so diverse, it was difficult to generalize about a “fix”. Since that assessment, state and local health departments have weathered additional, substantial cuts in resources and staffing, while concurrently battling a global influenza H1N1 pandemic.

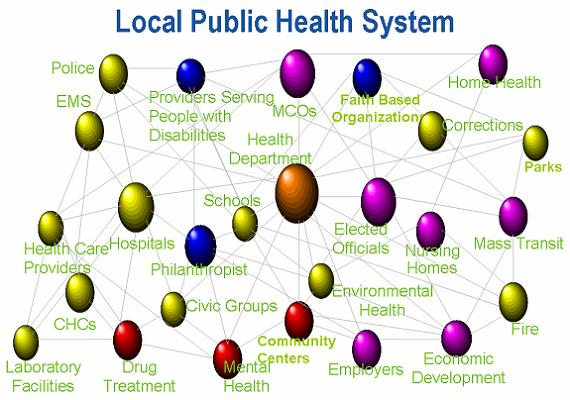

We believe it is time for a systemic solution, rather than a piecemeal approach to shortages in staffing, resources and training at multiple levels in each state. Whether they know it or not, every health care provider is a part of the public health system. If every training program for health care professionals provided a basic orientation to essential public health roles and training in basic competencies, the diverse U.S. health care workforce could begin to fulfill its essential public health roles in daily delivery of health care services. This would also expand the available pool of public health workers to staff health departments at all levels in all states, and assure a competent and capable public health system to protect our population from preventable disease and injury, and premature death. By including basic public health knowledge and related competencies in all board and licensure exams for health care professionals, we can begin to assure a competent public health workforce that includes all health care professionals.

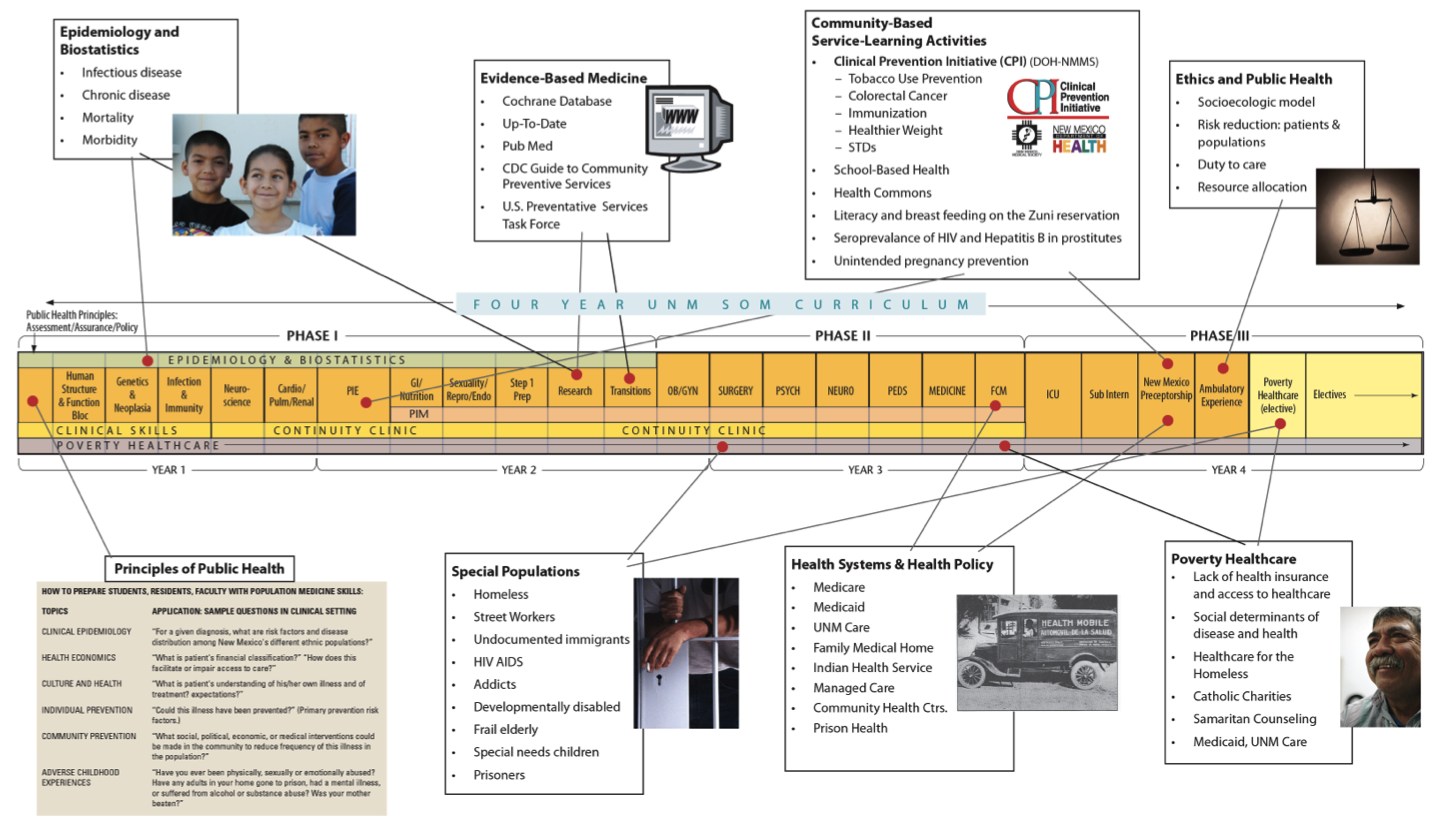

At University of New Mexico School of Medicine (UNM SOM), this systemic solution has already begun. Since the fall of 2010, all medical students are required to complete course work for a public health certificate (17 credit hours) to receive an MD degree, and training in essential public health competencies is being integrated into ward rotations.